So, on Day 3 after activating my other ear, here’s what I know so far:

1. The implant works. Good strong neural response to all electrodes.

2. It can understand speech when aided by reading cues, and it gets bits and pieces of uncued speech.

3. It helps a lot in noise.

So today I’ve been wondering why speech sounds so eerily real but not yet understandable, for the most part. I’m not impatient; it took weeks for me to get to this point with the other ear, back in 2001. Progress has been terrific. But it’s a neurological mystery. Today I’ve done some detective work.

To start with, I decided to listen to Winnie-the-Pooh and Some Bees to figure out what, exactly, my right ear is hearing.

My overriding impression is that speech sounds abrupt and shortened – as if words that actually take 100 milliseconds to say had been shoehorned into 70 milliseconds. Another way to put it is that it feels like pieces of the words are missing.

It’s like watching a squirrel. Instead of smooth glidings from one position to the next there’s discontinuous jumps, as if random frames had been edited out of reality.

But the “editing” isn’t so random. I listened closely to one passage and wrote down what it sounded like to me. Here’s the original:

It is, as far as he knows, the only way of coming downstairs, but sometimes he feels that there really is another way, if only he could stop bumping for a moment and think of it. And then he feels that perhaps there isn’t. Anyhow, here he is at the bottom, and ready to be introduced to you. Winnie-the-Pooh.

And here’s what I hear with my right ear:

It is, as fur as he knuzz, th’ only wy of coming downstrrrs, but sumtimes he fils that there rilly is another wy, if only hih could stop bumping for a moment and think of it. And then he fls that purhaps there iznt. Unyhw, here hih is at the bottom, and ready to be intriduced to yu. Winnie-the-Pooh.

Instead of hearing that long orotound o – as in knooows – I hear an abrupt foreshortened version of it: knuzz. It’s not that the word is actually shorter, although it sounds that way. It’s that the percept of the o is missing or incomplete. The speech sounds brittle and chopped up.

It throws me off enough that I can’t follow the sense of the soundstream. But, as you can see, there is plenty remaining, which makes it very easy to follow if I’m reading along with the text. And peculiarly, there are isolated instants of lucidity: the long o in Pooh comes through loud and clear.

Now, here’s the crux of it. I listened to the same passage just now with my left ear, which has been online and working since 2001. All the vowels were in their proper places sounding like their normal selves. Nice long o’s, good proper even a’s. I can understand the tape perfectly well. So the vowel-decoding software is functioning just fine in my brain.

What’s going on? Let’s consider the possibilities.

Possibility 1: The right ear’s software is not giving me vowel information. I doubt this. It’s the same ‘ware as is running in my left ear – 16-channel Hi-Res P – and the map is approximately the same. If I could put my right processor on my left ear (which I can’t, as each processor is keyed to one specific implant), my left ear would hear pretty much the same as it’s hearing now. No, the information has to be there. Which brings us to –

Possibility 2: My auditory nerves aren’t picking up certain kinds of information. They’ve been unused for many years. But neural atrophy seems to be only a partial explanation at best, because I’m hearing consonants and environmental sounds. Not only that, neural response telemetry showed that the nerves are responding strongly across the board.

Possibility 3: My brain is getting the information but doesn’t know how to use it. It seems to me that this has to be the case. But why, if my brain already knows how to interpret neural input coming from 16 electrodes refreshing themselves 5,156 times per second?

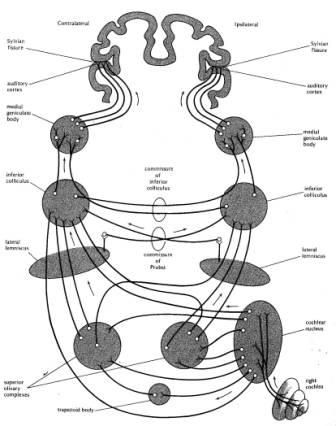

It’s well-known that the right ear sends most of its signal to the left hemisphere for high-level processing, and that the hemispheres have only partial access to what each other knows. But there is significant crossover as the signal ascends neural pathways to the auditory cortex. A quick glance at a diagram from Yost’s Fundamentals of Hearing makes that clear. (It’s the 4th edition, 2000, p. 228.)

The cochlear nucleus – the auditory’s nerve’s terminus in the brain – sends signals to the right superior olivary complex as well as the left one. The inferior colliculus on both sides are connected to each other, too. Basically, the right ear’s input makes its way to the auditory cortex on both sides, although the path on the right side is more convoluted.

I’m guessing that the echo I’ve been hearing comes from crosstalk between the right and left halves of my auditory system. As I noted in an earlier entry, my left ear rings whenever sound goes into the right ear. Right now, as I’m typing, each keystroke is followed by a bright ringing sound in the left ear that takes 3 to 5 seconds to fade.

This is a mystery for two reasons. First, why is it happening at all? And why do I hear the ringing in the other ear this time, whereas before, in 2001, I heard it in the implanted ear?

One wild idea I’m having is that some of the missing vowels are in that ring, somehow. (It’s reduced by about 50% when the left ear is active, by the way. Then it sounds like a brief bright chime.) The ringing did go away last time – so I’m paying careful attention this time to see if it happens again, and when.

To answer Jeff’s question in my last post, pitches do sound different in both ears. Music sounds different, in that certain pitches I hear with my left ear are less “pure” in my right ear. I’m not sure which pitches are different, because I tend to be poor at identifying pitch, especially on Hi-Res 16. (I’ll explain in a later post why I’m using Hi-Res 16 in both ears at the moment instead of Fidelity 120; it’s a strategic decision to scale down the complexity of mapping two ears.)

I spent about an hour studying Fundamentals of Hearing this afternoon. Now I’m going to try a different tack: I’m going to walk about town and hang out at Dubliner’s on 24th Street for a while, and see what happens. Perhaps a pint of Fat Tire will bring illumination.

Wow, Mike, you have been busy writing about your experiences going bilateral. I sure enjoyed reading it all and of your speculations why your new ear isn’t up to par yet even though all of your electrodes are firing. You have a way of putting things into words that I haven’t been able to articulate. By the way, great choice to read a selection from Winnie-the-Pooh! 🙂

Michael,

Wow! How can you write this blog with ease in elaborating and describing what you are hearing and feeling? I’m a writer as well, but it boggles my mind– creative blockage as they say. Regardless, I’m going bilateral on Feb 5th, my activation day. (Yep, I got my second ear implanted on Jan 10th)

Well then, keep in touch! I was this wheatish-complexion young lady you met at Gallaudet, and we spoke of our deafness to starting a book. Hope you remember me!

Zahra

I just started wondering something else. Since 2001, your brain has been accustomed to the electrode’s insertion in the left at a specific depth (knowing that deeper or shallower even a single millimeter can have a significant effect on the perception of sound). If, therefore, the electrode in the right has been inserted at a slightly different depth as compared to the left, then perhaps that makes it a whole new ballgame for your brain to deal with.

Steve: Insertion depth in relation to pitch perception is something I am very interested in — hence my question for Mike. I discussed some of the issues in a recent entry in my blog. Current CI programming software does not have the capability to adjust the center frequencies of the electrodes to correct pitch perception. I am investigating why not, but I believe one reason is that there is some evidence that the brain can adjust on its own. But if it doesn’t, there is no reason why a feature to adjust it in software could not be added in the future. There are already frequency compression hearing aids that transpose pitches. Even though I am not bilateral, I strongly suspect this issue could be of importance to those that are.

Steve, that’s a very interesting question, and Jeff’s thoughts on it are to the point. I wouldn’t be surprised if the brain could adjust – my own voice went from sounding scratchy to sounding deep within a day after my first activation in 2001.

I never thought about the possibility of a mismatch. But since there’s nothing I can do about the electrode placement, I’m marching on. 🙂

You definitely do have an electrode mismatch. Your new electrode is precurved & was not available when you first got implanted. Plus there are insertion depth issues also.

This will give you the pitch mismatch Jeff described and will cause vowels to sound different.

“Somehow” the brain will learn to deal with it.

One more thing: I am not implying that an sort of error was made during the surgery. As far as I know, there is currently no reliable way for the surgeon to precisely place the electrode array in relation to pitch perception. I suppose they could wake us up in the middle of surgery and ask if a particular tone sounds like an A-440, jiggling it in or out until it did — but I’d rather not go through that 🙂

If the brain can’t quite fix it, software is the answer. My dream array would have electrodes from base to apex, and then the software would be capable of re-targeting the pitches as necessary.

Interesting that Another Mike mentions vowels. Since my pitch perception is lower than what I recall as normal, I have more trouble with men’s voices in general. I think it is due to the deeper vowels. They tend to get “lost” in noise easier, or mush together. But I’m still at the early stages (activated less than 2 months) and this could all change.

Glad you made that point about it not being due to the surgeon, Jeff. The cochlea is the size of a pea, and there’s no way to control insertion depth precisely enough to match frequencies on both sides. Besides, there are almost surely small differences in the anatomy of each cochlea that would render such an effort moot even if it could be done.

Your writing these days are highly interesting! I’m learning a lot from you, and also from Jeff about the technicalities of sound (and teh workings of HI-res CI). It certainly will help me when I get there, having a decent vocabulary to describe sounds and their workings 🙂

I already asked a technician at the hospital if it is possible to tweak your own hearing at home, but that’s a NO-NO 🙂

(danger of overload, and possible permanent damage to the nerves was the explanation)

I also plan to purchase newer audio equipment for my PC in preparation, a music keyboard and new speakers. So I can play with the sounds before and after the implantation. (it’s incredible what the PC can do with sound! Ever tried Steinberg Cubase?)

Oh, and I have a suggestion for you:

You write about your right ear not picking up certain parts of the words from Winnnie-the-Pooh… I think that reading out aloud and speaking to yourself could be good training… Do you do that? Did you do it to your first ear?

I have noticed from reading Harry Potter-books to my son, that I also get exhausted from listening to my own voice, I think that maybe our own voice is the ultimate sound-calibration tool? We know it inside and out….

Over 2 years after the original comments here, it is nice to revisit. My brain did indeed adjust for my pitch mismatch issues that bothered me in the early months following my implantation. At about six months the change became quite noticeable. By 1 year I felt I was getting back to something approaching normal. Not only has the overall shift taken place, but I strongly suspect that my brain has made finer adjustments between individual pitches — because music went from quite awful, to quite listenable. It is not perfect, but certainly far, far beyond my expectations.

Hey Michael,

I am a graduate student and the focus of my dissertation is on the synaptic mechanisms of binaural interactions in the auditory cortex of rats. I know that rats aren’t humans, but mammals have many similar neural circuits. I’m currently making a presentation for lab meeting on Friday and I’ve been hand drawing the same auditory map you posted from some of the original ablation papers. The circuit is quite complicated, but fascinating. I loved reading your post. While reading it, I realized that I read many papers on animal studies, but I have spent almost zero time reading first hand accounts of hearing deficits or tinnitus in people. I am very interested in hearing loss and tinnitus. I served in the Navy a while ago as a Hospital Corpsman and one of my duties was to give hearing tests. Lots of men had tinnitus, from all that shooting.

Thanks for the post.

Michael Kyweriga

Wehr Lab

Institute of Neuroscience

University of Oregon