In this blog entry I’ll be offering my early impressions of a new cochlear implant processor, having used it for two weeks. It is a complex technology and I expect it will take me quite a while longer to master all of it. I plan to update this review as I gain more experience with it. (I have written an update, as of March 10th, 2014. It’s here.)

Summary: The Naída CI Q70 is a new cochlear implant processor built in a collaboration between Advanced Bionics, a maker of cochlear implants, and Phonak, a maker of hearing aids. It offers many valuable new features. The Bluetooth connectivity is a standout, particularly for music. Some of the special-purpose software features are difficult to learn and use.

The Pros: Smaller and lighter than previous processors. Excellent support for bilateral hearing. Excellent music processing. High degree of control over settings. Bluetooth connectivity to other devices through the ComPilot.

The Cons: Expensive. Difficult to learn and use. Slow program switching. Cramped interface design, particularly in the myPilot (the remote.) Incomplete documentation. No Bluetooth connectivity in the processor itself.

Cost: Approximately $19,000 for a pair of two, depending on exact configuration of batteries and accessories. Much of this should be covered by insurance. I have discussed the financing elsewhere.

Here is a picture of the Naída CI Q70 on my right ear.

As you can see, it’s the part of a cochlear implant that stays outside the head, sitting on the ear like a hearing aid. It takes in sound and converts it into data. It uses its radio transmitter – that’s the round part – to send the data through the skin to the chip embedded in the skull. (It’s underneath the skin, so there’s no break in the skin.) The chip passes the data on to the auditory nerve in the inner ear. From there the data goes to my brain, which hopefully will sort it all out.

The chip inside the head can’t be replaced. Well, actually, it can, but that’s done only if it fails, and it means having surgery, which no one takes lightly. So to upgrade a cochlear implant you replace the outer part, the processor. A better processor can, in theory, send better data to the chip, enabling the user to hear better. That’s why new processors are a big deal to cochlear implant users.

I’ve gone through four generations of processors since I was implanted in 2001: a belt-worn processor the size of my palm, a first-generation behind-the-ear processor, a second-generation Harmony, and now the third-generation Naída. (I described the process of getting a cochlear implant in my first book, Rebuilt: How Becoming Part Computer Made Me More Human.) To make the Naída, Advanced Bionics joined forces with Phonak, a maker of high-end hearing aids. Phonak took one of their existing hearing aids, the Naída Q70, and worked with Advanced Bionics to convert it into a cochlear implant processor – the Naída CI Q70.

What new things does it do? How well does it do them? And is it worth the cost and learning curve?

Let’s start with the form factor – the size and shape of the processor itself. The Naída is smaller and lighter than its predecessor, the Harmony. This is especially welcome for children and people with delicate ears. (I’ve known users whose ears got so irritated by older processors that they had to use moleskin to prevent chafing.)

Smallness does have one drawback. The controls for volume and program are tiny and hard to tell apart. It took three days for my fingers to figure them out. I would suggest that AB add a texture to the up-volume button to make it easily distinguishable from the others. (This is partly mitigated by having a remote control, which I’ll be discussing later.)

The program-switching button lets you switch between five programs. That’s a big advantage over the Harmony, which only has three. The extra slots let me have more programs for specific environments such as noisy places and music. They also let me try out more programming variations to see which work best.

There is, however, a big problem with switching between programs. By my stopwatch, it takes 6.6 seconds for the Naída to switch from one program to another. That’s an eternity if you’re watching TV or talking to someone, especially on the phone. Waking the processor up from standby mode takes even longer: 10.6 seconds. It takes me 31 seconds to go from program 1 to program 5. The remote, which I’ll discuss later, helps a little. It lets me jump straight from one program to another – say, from 1 to 4 – but the interval of enforced silence is still 6.6 seconds. Slowness discourages users from switching, which undermines the point of having multiple programs. Ideally, it should take no more than half a second for the processor to wake from standby and switch programs. (Update 3/5/14: I’m told that AB plans to release a software fix to reduce the switching delay.)

An extremely nice feature is that either processor can go on either ear. The processor auto-detects which ear it’s on and invokes the programs it has for that ear. This is terrific for two reasons. First, whichever processor I find first in the apartment is the one I can put on my left ear, which is my better ear. Second, the processors serve as backups for each other.

In fact, the processors not only figure out which ear they’re on, they also exchange information with each other by radio. When you change the volume on one, it also changes the volume on the other. For me this is a very important feature because it keeps both of my ears online. I tend to ignore my right ear, which was always my worse ear. I often turn down its volume and then forget to turn it back up. With the Naída system the ears stay matched, and it makes me get more value out of the right ear.

I got T-mikes of two different sizes, the regular size and the pediatric size, to see which would fit better. (The T-mike is a cleverly designed mike that sits inside the shell of the ear, using it to focus sound.)

For me the pediatric size is a better fit, as you can see in the pictures. Teens and women may do better with the pediatric size as well. This could be renamed the “small” size so that adult users don’t overlook it.

The processors are water-resistant. The manual says that they are rated IP57, which means that they are “protected against failure due to immersion for 30 minutes up to a depth of 1 meter.” Nothing is said about what would happen if I stayed in the water for 31 minutes or swam down to 1.1 meters. Given how much they cost, I’m unlikely to test that IP57 rating. Rumor has it that Advanced Bionics plans to release a waterproof enclosure for them. In the meantime, I may try swimming with an old Harmony processor with this clever technique for protecting it.

How does the Naída sound in quiet environments compared to the Harmony, without special-purpose programs or accessories? My audiologist took my settings on the Harmony and simply transferred them over. I can’t say I notice any difference in ordinary sounds: my voice, my wife’s voice, the clicking of keyboard keys, cars, our cats – they all sound pretty much the same as before. This doesn’t surprise me. With speech in quiet, either you understand it or you don’t. I understood speech in quiet very easily with my Harmony processors; in essence, for me this is a solved problem. From a new processor I would hope for better performance in noisy and challenging environments, such as restaurants and cars, and when listening to music, which has a much larger frequency range than speech.

That’s why I focused my attention on (a) the special-purpose features and (b) the accessories. Let’s start with the special-purpose features.

Special-Purpose Features

Special-purpose programs are designed to help in specific situations. I was given three: UltraZoom, ZoomControl, and DuoPhone. Each one has to be put in a program slot of its own, so you have to manually turn it on when you want it. There are two others called WindBlock and SoundRelax, which I don’t have. Maybe they’re in Europe only?

Before we go any further, I am going to do some renaming. Having features named “UltraZoom” and “ZoomControl” is confusing for everyone, including my audiologists. From now on I’ll call UltraZoom “ZoomAhead” and ZoomControl “ZoomToSide.”

ZoomAhead is supposed to do clever things with the processor’s microphones (there are four of them) to selectively amplify what’s in front and suppress what’s behind and beside. The technical name is “beamforming.” The idea is to reduce surrounding noise in places like restaurants. The Phonak hearing aids I had in 2001 had this feature, and I loved it. I was very sorry to give it up when I transitioned to cochlear implants. I’m glad to have it again in the Naída. However, I haven’t gotten much benefit out of it yet. I’ve tried it in three environments so far: a book discussion group of about fifteen people, a room with a vacuum cleaner running, and a restaurant. In each case, I couldn’t find an auditory “sweet spot” ahead of me in which a person speaking to me sounded especially clear. I was accustomed to finding this sweet spot with my old Phonak hearing aids back in 2001. Clearly, I have not figured out this feature yet, and will update this if I do. (I have figured it out. Update here.)

ZoomToSide is supposed to be for places like the car, in which the user’s better ear may be away from the driver or passenger. The manual describes it as “streaming from one processor to the other,” but it’s hard to understand what that means in practical terms. I haven’t tried it in the car yet, because my wife and I rarely drive together. But here is a situation in which ZoomToSide unequivocally helps. When I’m lying next to my wife in bed with my good ear in the pillow, I can’t understand her at all. I have almost no speech discrimination in my bad ear. That means I often have to get up and move to her other side so the good ear can be up. So I turned on ZoomToSide and lay down with my good ear in the pillow. I then used the Controller to set the bad ear as ZoomToSide’s “focus.” And then I discovered that I could understand her fine. Clearly, ZoomToSide was sending microphone data from the bad side to be processed on the good side. (Now, how about an iPhone-style gyroscope in the processor so that it knows its orientation and switches on ZoomToSide accordingly? I’m half-joking, but…hmmm.)

ZoomToSide’s user interface on the Controller is very confusing. I finally figured out that there are two separate ways to turn on ZoomToSide, and that it turns off when the user would reasonably think it’s still on. The feature needs an improved interface design.

In DuoPhone, the output from the phone (or anything else, for that matter) is sent to the other processor as well, so you hear the phone on both sides. Like ZoomAhead and ZoomToSide, DuoPhone lives in a program slot of its own, so you have to go to that program to get the effect. Nice idea, but in my case not really necessary, since for most phone calls I use Skype with a headset, so I get the voice on both sides anyway. But I’ll be trying it out in the world with my iPhone and I’ll report back.

Accessories

So far I have gotten more benefit out of the accessories. I got two, the myPilot and the ComPilot. There are others, but I think these are the most important. Their names are confusingly similar, though, and neither gives a clue what they actually do. So for the purposes of this review I’m going to rename them.

This is the Controller (aka the myPilot). It’s a remote that controls the processors.

This is the Connector (aka the ComPilot.) It connects the processors to things.

Their functions overlap somewhat. Both the Connector and the Controller can change the volume and the program. However, their individual functionalities are so different that I think it’s necessary to have both. I often use them at the same time, e.g. for making adjustments to the processors while I’m using the Connector to listen to music.

The Controller lets me change the program, the volume, the sensitivity, and a host of other things, and it has a display that shows me what the current settings are. Of these settings, sensitivity is the most helpful. My first processor, the belt-worn one, had a sensitivity dial, and I found it very useful. I was disappointed that my next two processors had no way to control sensitivity, so I’m delighted to have that feature back with the Naída.

By cranking up sensitivity, you can pull in the really soft sounds. The air conditioner vent in the corner, the conversation a hundred feet down the hallway. Nothing becomes louder, you just hear more sound overall. In daily life high sensitivity isn’t usually helpful – it tends to be overwhelming – but it is enormously beneficial for music, where detail is critical. More on music shortly.

The Controller is very useful, but it’s tedious and complicated to use. The screen is so tiny that you have to scroll through levels and levels of menus to get to what you want to change. There are other pesky little problems. When I change my program or volume on my processors, the Controller won’t know it until I press its power button to force it to update itself. I was very confused until I saw that point in the manual.

I think the Controller dates back to 2008. Now that it’s 2014, can an iPhone/Android app be written to replace it? I’m not sure if this is possible with the Naída, for various technical reasons, but it would be extremely useful to be able to control my processors through my smartphone. One less thing to carry, one less thing to lose, and much more screen real estate.

Now I’ll discuss the Connector. In the past week I have spent far more time using the Connector than anything else. There is one thing the Connector is fantastically good at, and that is music.

Music with the Naída Processors

To understand my experience with the Naída you have to know my history of hearing music. Here’s a short account, in which I quote from things I wrote at various times.

I was born with severe hearing losses, and wore hearing aids between ages 3½ and 36. Even so, I could hear music well enough to enjoy it. In an essay looking back on hearing aids I wrote,

When I was fifteen I listened to Ravel’s Boléro many times, lying on the living room couch with my eyes closed. For me Boléro was a poem of ascent and decline, glory and futility. For the upslope of each arc, the crisp sharp cry of flutes; for the fall back to earth, bassoons and oboes. The descending side of each arc was always the most memorable for me, bringing to mind a stream waterfalling stair-step to linger, briefly, in a still pool. (This essay is in Deaf American Prose, volume 1. A shorter version was published in Wired in 2005.)

At age 36 I went totally deaf (cause unknown) in the summer of 2001, so I couldn’t use hearing aids anymore. Hearing aids just amplify sound, so if you’re totally deaf they’re useless. I got my cochlear implant in the winter of 2001. In many ways the implant let me hear even better than before, but not for music. The implants were designed to process speech, with music being an afterthought. I lost that ability to feel immersed and enraptured by music. I tried listening to Boléro, but the experience fell devastatingly flat.

I found immediately that I could hear the percussion as well as ever. There was the familiar da-da-da-dum! da-da-da-dum! da-da-da-dum-dum-dum! played insanely over and over, sounding exactly as before. But the timbre of the instruments sounded flat and dull. The flutes’ intense keening arc sounded truncated and faded, as if someone had clapped pillows over them; the mellow bassoons sounded like the charmless groans made by rickety furniture. I was getting the structure of the music without the melody that made it worthwhile. It was like walking colorblind through an art museum. Time and practice made no difference. Books-on-tape became clear and crisp within the first three months, but music remained as flat and stale as ever. I began to feel like a curious extraterrestrial while browsing through radio stations. “This is what you Earthlings listen to for enjoyment? This is a sensation that gives you pleasure, yes?”

At the time I was using the body processor, whose software gave me eight channels of auditory resolution. That’s not much. By comparison, a normal ear has effectively thousands of channels. Shortly afterward I got the first behind-the-ear processor and upgraded to new software that increased the resolution to 16 channels. (No surgery was involved. This was done by downloading new ‘ware into the processor.) Music sounded a little better, but not much.

That was where matters stood in 2002. Over the next two years I tried different kinds of software in labs around the country to see if I could hear music better. What worked the best was Advanced Bionics’ own new software, titled Fidelity 120. Through fancy software tricks it made my ear believe that there were 121 electrodes in my cochlea instead of 16. That gave me better frequency resolution, letting me hear tonal distinctions I couldn’t before. In my 2005 article in Wired I wrote,

At 5:59, the soprano saxophones leap out bright and clear, arcing above the snare drum. I hold my breath.

At 6:39, I hear the piccolos. For me, the stretch between 6:39 and 7:22 is the most Boléro of Boléro, the part I wait for each time. I concentrate. It sounds … right.

Hold on. Don’t jump to conclusions. I backtrack to 5:59 and switch to Hi-Res. That heart-stopping leap has become an asthmatic whine. I backtrack again and switch to the new software. And there it is again, that exultant ascent. I can hear Boléro‘s force, its intensity and passion. My chin starts to tremble.

I open my eyes, blinking back tears. “Congratulations,” I say to Emadi. “You have done it.” And I reach across the desk with absurd formality and shake his hand.

That was a major advance for me. But it still wasn’t as good as what I’d heard through hearing aids. Toward the end of the article I noted,

Both compositions sound enormously better on 121 channels. But when Rettig plays music with vocals, I discover that having 121 channels hasn’t solved all my problems. While the crescendos in Dulce Pontes’s Canção do Mar sound louder and clearer, I hear only white noise when her voice comes in. Rettig figures that relatively simple instrumentals are my best bet – pieces where the instruments don’t overlap too much – and that flutes and clarinets work well for me. Cavalcades of brass tend to overwhelm me and confuse my ear.

Listening to Boléro more carefully in Rettig’s studio reveals other bugs. The drums sound squeaky – how can drums squeak? – and in the frenetic second half of the piece, I still have trouble separating the instruments.

I got my other ear implanted in 2007. I hoped that music would improve once I could hear in stereo. And it did. In 2008, I discussed my experience in the Journal of Life Sciences. I wrote,

And then I tried music. I started with Debussy’s Clair de lune, a slow, reflective piece played by an oboe and a harp. I could feel the new ear feeding me its version of the soundstream. It didn’t sound as limpid and clear as the left, but it was giving me music, mirroring the left. Mirroring? Actually, no, I realized. The headphones were shifting the sound intensities back and forth between them, playing off of each other.

Stereo.

And I was caught up in it: following the contours of the piece, its wholeness, its probing of the emotional resonances of sound; a moonlit glade with the stars wheeling overhead.

“It sounds lovely,” I breathed.

Wow.

It held my attention the way a good story does. I listened to it three more times, once with only the right, once only with the left, then once with both again. Disassembling and reassembling the piece.

I realized that listening to music with one ear is essentially pointless. Music reaches into you and works on your brain. To do that, it needs to work on all of the brain. Hearing music with only one ear engages only half of the brain. Hearing Clair de lune with two ears was like the difference between a live and a dead body: the form was the same, but the experience was oh so different.

By this time I was wearing the second-generation behind-the-ear processors, the Harmony processors. They also also solved the “whiteout” effect I’d heard with Dulce Pontes’s voice. The drums didn’t sound squeaky anymore either.

Despite those many improvements, I never became a daily listener to music. It remained peripheral to my life. There were two reasons. First, it still wasn’t as good as what I’d heard with hearing aids before I went totally deaf. The frequency resolution of my cochlear implants was just not good enough. And while I could hear the beauty in the music, it still didn’t give me that encompassing thrill that captured my attention and did not let go. The timbre, the clarity, the sheer exhilaration of tonality, the presence, just wasn’t there.

Second, with the Harmony processors, getting set up for listening was a pain. The best way to listen was direct-input, where the signal went directly from a CD player into my processors. This required screwing off my T-mikes and replacing them with input connectors, and then plugging those into a Y-adapter, and then plugging that into the CD. To talk to anyone I had to undo the whole process, getting the T-mikes back on and rebooting. Too much pain for not enough pleasure.

I did enjoy music when I came by it. At the Conference on World Affairs in Boulder in 2009 I went to a jazz concert and was delighted by it. My wife and I go to the Kennedy Center for holiday music and I usually enjoy it. But it was a hit-and-miss sort of thing. I never bothered to use iTunes on my iPhone.

So when I first used the Naída for music, it took me a while to find iTunes. It took me a while to figure out the Connector, too. First, you have to pair it with the processors. Fortunately, that only has to be done once. Second, you have to set up the Bluetooth connection to the iPhone. Bluetooth is a way of wirelessly connecting devices. That only has to be done once too, although the iPhone seems to need to be reminded to make the connection sometimes. Third, I used the Controller to pick the program I thought would be best for music. That’s three handheld gadgets to juggle. But finally I got Dulce Pontes’s Canção do Mar streaming wirelessly into my processors via Bluetooth. Canção do Mar is a good piece for testing because it ranges from very soft to very loud, has easily distinguishable instruments, and the singer’s voice stands out very clearly. Plus, it’s a lovely piece of music.

First I adjusted the volume and sensitivity. I quickly rediscovered that for music, high sensitivity is generally good. It lets me hear the subtle details. There is a drawback – sometimes I also hear a background hiss. Sometimes I don’t, and I’m confused about why. But on the whole, sensitivity is good.

Once I began really listening, Canção do Mar took hold of me and did not let go. There is a kind of atmospheric sighing at the beginning, like listening to a fog-filled forest. After about thirty seconds the melody comes in, with bright pure chimes like diamonds. Then there’s a series of crescendos, like waves crashing into a seawall. Dulce Pontes’s voice comes in at about 1:30, in Portuguese. Pontes’s voice weaves in and out of the music, voice and music giving way to each other in a beautiful kind of tapestry. It lived up to my auditory memory of the song: the purity of the diamond tones, the buttery-soft cadence of Pontes’s voice, the gorgeousness of individual notes. I remembered that it sounded this way, but I had not actually heard it this way since I went deaf in 2001. It was like the difference between remembering a painting and actually seeing it. I had not heard music that sounded really good for 13 years, and it took my breath away to have it back.

What made the experience so good? I think it is a combination of things. There is the direct input to the processors, which improves the signal-to-noise ratio and blocks out environmental sounds. And I think, but don’t know for sure, that the processor is also handling the sound itself better than the Harmony. Not being a sound engineer, I couldn’t possibly explain the details of why. I have tried comparing them, and I discuss that below. (I’ve also tried listening to music through my AblePlanet Linx Audio headphones. I’d say it sounds about 80% as good.)

I spent the rest of the day downloading songs onto my iPhone. My right ear sounded – well, it sounded odd. It seemed to turn on and off during a song. After a while I figured out that the soundtrack was parceling out sounds between right and left to create a stereo effect. Now and then I would lift the left headpiece off so I could hear only the right ear, and it was clear that it was hearing a much-degraded version of the song. But the ear added to the totality of the sound. It added quite a lot.

Compared to what I’d heard on the Harmony, it sounded superb. Absolutely fantastic. For the next three days I did little but listen to music. I listened to various songs over and over again, working out which programs, volume levels and sensitivity settings were best.

On the fourth day, I woke up to discover that music suddenly sounded flat again. I went to an audiologist. It turned out to be an easily fixable software problem. The volume control on my right ear had been turned off so that nothing happened when I clicked up or down. How exactly that happened, I don’t know.

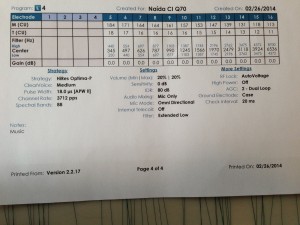

We also decided to set up a program specifically for music. She set its input dynamic input range to 80. Input dynamic range is basically how much of the frequency range the processor takes in. The higher the IDR, the more sound the processor captures. ClearVoice was set to medium (rather than high, where I’d had it set before.) ClearVoice tries to decide what’s noise and filter it out, which is good for speech but may not be so good for music.

In short, she fixed the right ear and possibly improved both of them. The right ear was back online, contributing to my stereo hearing in its zaftig but helpful way. I went to a book club meeting in downtown D.C., and then I went home streaming music into my processors via Bluetooth. As I walked into our apartment building, my iPhone started up Michael Jackson’s You Are Not Alone. It sounded so lovely that I stood in front of our door without going in, not wanting to stop listening to the music. You are not alone, Michael Jackson crooned. I am here with you / Though you’re far away / I am here to stay.

When the song ended I went inside, kissed my wife, hung up my coat, and playfully stuck my nametag onto our cat Posy. Posy leapt up as if electrocuted and ran around the apartment in dismay, trying to get it off. Tory ran after her. I followed them both into the TV room, giggling.

“Are you…drunk?” Tory demanded of me after getting the nametag off Posy.

“I had one beer,” I said. “No, I’m not drunk. But I am intoxicated. On music.”

I wondered how much of the improvement was really due to the Naída. Would I do as well if I reassembled my old apparatus for direct-input to the Harmony, my old processors? I tried it out, using a CD of Canção do Mar (it’s on the soundtrack of the movie Primal Fear.) It was not an entirely fair comparison. I can’t raise the sensitivity on the Harmony. And my Harmony programs have an input dynamic range set to 60, whereas on the Naída it’s set to 80.

I listened to Canção do Mar twice on the Harmonies. It was very pretty. Then I switched to the Naídas and listened to it again. Here is what happened: a surprised jerk of my head as the instruments came in. It felt like the music had jumped closer and grabbed my collar. It was more intense. Purer and more emotional. Could that be duplicated on the Harmony processors? Maybe; I could have my audiologist back-program them to match my Naída settings. It would be worth a try. But the most salient fact is this: when I got my Harmony processors in 2007 or so and started listening to music, I didn’t do it for six-hour stretches at a time. I blogged about it, but not like this. I wasn’t back in the audiologist’s office three days later demanding more. Also, with the new processors it’s much easier to set up direct-input, and ease of use makes a real difference.

I’ve been improving my music perception bit by bit since 2001. It may be that I had to reach a certain level of quality before music really became worth it. The Naída plus the Connector might be only 10% or 20% better for music than the Harmonies. But those small improvements have thrust me into a rediscovered world.

Every Piece Of Music I Love

Every piece of music I love, I have discovered by accident. Not as a result of sustained lifetime listening. Not as a result of being tutored by a gaggle of friends in school. I know Gloria Estefan’s Live for Loving You because it came for free as a music video on a Toshiba laptop I bought in the mid-1990s. I know Canção do Mar because a friend of mine, Jennifer Morley, played it in the car while we were driving somewhere in Austin. I know Aura Lee because my parents had, for some reason, an LP of Civil War songs by the Mormon Tabernacle Choir. I know Michael Jackson’s You Are Not Alone because I watched a documentary about him. I know Sills and Young’s Long May You Run because I heard it on the documentary My Architect, in the scene where Nathaniel Kahn strapped on a pair of skates and cruised around the building his father designed for the Salk Institute. I know Suzanne Vega’s Ironbound/Fancy Poultry because my friend Jeff Weill played it for me once at his house. I know the Beatles because my brother Dan had their albums. I know Blue Danube via 2001.

In the past week I have collected all of these songs on my iPhone, heedlessly running up the bills on iTunes. It is a rather sad gallimaufry of music: a handful of random songs, revealing no clear preferences. I know essentially nothing about genres or time periods. There is classical and there is rock, and that is all. Were the eighties a good time for music, or do people look back on it like they do seventies clothing? Was INXS good? What were the Eurythmics all about? Why is Daft Punk a big deal? I am an adult man in his late 40s who does not know what “key of D minor” means. I wonder about my tastes. Would an audiophile look at my collection and patronize me, the way I would, just slightly, if a blind man with a retinal implant gushed to me about being able to read Danielle Steele? I have been out of it for a very long time, and I am coming to a common pleasure late in life.

And incompletely, at that. My ears are terribly mismatched. I fine-tuned my left ear’s programming very carefully over the last 13 years, but more or less ignored the right. I have a little electric piano that I bought on Amazon for fifty dollars. In the right ear, each key sounds completely different in pitch and in volume than it sounds to the left. The right ear has much poorer frequency resolution, too. With my left ear I can tell adjacent keys apart. With my right, adjacent keys sound the same. It’s only when I hit a key three or four keys away that it can hear the difference.

My right ear helps in music – critically so – but it is still very ill-suited to the task of stereo. I’ll work with my audiologist to improve it, but I don’t know how much to expect. I can give my brain a better signal, but I don’t know if my brain will be able to use it. (I have been working on the right ear. Update here.)

But even with a spiffed-up right ear and more practiced brain, and maybe another generation or two of software on the Naídas, will I really know what music is? For complicated reasons I won’t get into here, I use only twelve of my sixteen electrodes in the left, eleven in the right. (There’s nothing wrong with the implants. I just seemed to hear better that way in mappings I did between 2001 and 2007.) That gives me 88 channels of frequency resolution in the left, 80 channels in the right. That is at least two orders of magnitude below the resolution of a normal ear. Maybe I can now turn a few of those electrodes back on, and get closer to the maximum of 121. But still: I think of the men tied up in Plato’s cave, looking at the shadows on the wall and thinking them reality.

And yet, even with only 80 channels and mismatched ears, and the remote I have to fuss with and the hiss I don’t understand, it is like going from seeing in black-and-white with one eye to seeing in color with two. It is glorious. It is thrilling. It is intoxicating. It punches right through to my subconscious the way music is supposed to. Perhaps beauty has a certain minimum threshold, so that once one surmounts that threshold, one grasps it whole and full.

It’s hard to compare the Naídas to the music I heard through hearing aids, because 13 years have gone by since I went totally deaf. But I think it is very close, if not even better. The direct input from the Connector gives it to me pure, unmixed with the grubby sounds of footsteps and air vents and passing cars. I can hear nothing else while it plays, not even my own voice. No one else can hear it either, because there are no sound vibrations anywhere. It is going from my iPhone’s chips straight to my nervous system.

That means I am completely unable to share the experience with my wife. She knows I’m listening to music, but she hears absolutely nothing of it. I could play Canção do Mar acoustically for her on my iPhone, but then I wouldn’t hear it with the intensity and purity of Bluetooth streaming. And for her to hear it as subjectively loudly as I do, it would have to be played through gigantic speakers at top volume. We don’t have speakers like that, and even if we did, we live in an apartment complex and couldn’t impose it on our neighbors. And even if we did, I don’t think I would hear it “right.” As far as I can tell, music is something we cannot experience together. Folk philosophy tells us that ultimately each of us is alone. It’s beyond my scope to argue that here, but it is strange for it to be so concretely true in this particular case. It feels like having the Musée d’Orsay all to myself, permanently.

It has been very strange to ride the Metro with my iPhone and the Connector hidden under my winter coat, Boléro playing at top volume, roaring inhumanly loud. I think it would shake the walls of Metro Center’s concrete cave if it was played through speakers at that volume. No one on the train has any inkling what sensory intensities are contained within my compact little body. I see plenty of people with iPhone earbuds, and I wonder if I might actually have an advantage over them. What I hear is partial and distorted, but it is being injected intravenously into my soul, and that has to count for something.

I haven’t yet discovered any new songs that I like as much as my collection of old ones, the ones I heard through hearing aids. This past week has been mostly about joyful rediscovery. I worry a little that I will remain stuck in my auditory past, savoring only the tunes I first heard thirty years ago. My wife has a large collection of CDs. She has selected a small pile of them for me. They’re sitting on our kitchen counter: musical homework.

Overall Impressions and Looking Ahead

The Naída system strikes me as being both sophisticated and awkward. It is sophisticated in its support for bilateral hearing and in its superb processing of music. The accessories offer many new possibilities for managing hearing in different environments. They have also plugged me into the Apple ecosystem of music, and now I understand why iTunes makes so much money.

But it feels awkward in how much button-pushing and fussing I have to do to get everything working right, and in all the little electronic boxes I have to carry around. The processors frequently do unexpected things, like switching me from one program to another. Often I wind up with different programs running in each ear, and I have to fiddle with the Controller to reimpose discipline. And I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve had to hold up my hand to keep my wife from talking while I switch programs.

The reason it’s awkward is that I have to tell the processors what to do. ZoomAhead, ZoomToSide, and DuoPhone all have to be managed by hand. (I figure that WindBlock and SoundRelax do too.) I have to invoke the music program by hand and wait 6.6 seconds for it to kick in.

The processors really ought to be smart enough to figure out what is happening around me and change their settings accordingly. Why can’t they figure out that I’m listening to Blue Danube? Sitting in a restaurant? Hearing my wife talking in the passenger seat of the car?

The technique for doing that is called “auditory scene analysis.” People at Phonak have been studying this for years (for example, here). I hear it’s difficult to do and computationally expensive. I can’t speak to the difficulty of it, but if it’s computationally expensive, could that task be offloaded to a smartphone? Could my iPhone or a future iWatch have an app running in the background that monitors what the processors hear and sends commands that change their volume, sensitivity, program, and so forth? Naturally, the Naídas should still be able to operate on their own. (This feature now exists in hearing aids. Update here.)

And there’s a whole ecosystem of smartphone information that the Naída could use. Using Google Maps, couldn’t they know that I’m in a vehicle and switch to the appropriate program for that environment? What about voice commands? “Naída, sensitivity up.” Many of the pieces seem to be in place now: powerful mobile computing, Bluetooth connectivity, the ease of making apps, and voice recognition software.

The one missing piece is that the Naídas themselves don’t have Bluetooth connectivity. They get Bluetooth connectivity only when the user wears the Controller. That’s one more thing to carry around and fuss with. It seems very unfortunate that Bluetooth is not built right into the Naidas. Can that design decision be revisited? Or could a battery be made that has the Bluetooth wiring built into it? I would be glad to have a larger processor in exchange for smartphone control.

Is It Worth It?

So finally I come to the question of whether the Naída is worth the cost and learning curve for people who have the older Harmony processors. It is an expensive system. Two processors plus the Controller and Connector cost us $19,210. Fortunately insurance has paid for half of that already, and I have an appeal pending that I hope will take care of most of the rest. Furthermore, Advanced Bionics has a buyback program in which it will pay $1,900 apiece for up to two Harmonies. I have three, so I plan to sell two back and keep the third as a backup. In the end our cost won’t be higher than $5,000, and it may well be under $1,000. I’ve written a detailed report on our financing, which is still a work in progress as of early March 2014.

If you’re an adult with Harmony processors, and music is a priority, and you can manage the financing and the learning curve, the Naída is certainly worth it. However, I would ask if a new version of the Naída will be released with Bluetooth built directly into it, with the idea of enabling smartphone apps to control it. If so, it might be worth waiting for that. These technologies take a long time to bring to market because of FDA regulations, so it could be a long wait.

If you are a parent of a child with Harmony processors, and all of the above conditions apply, I would evaluate the Naída in the light of the child’s age, personality, cognitive capacity, and so on. The research makes it very clear that the better a child hears early in life, they better they will do in their entire lifetime. That makes the Naída well worth considering, but accessing its superior capacities is a challenge, particularly since you yourself will have no idea what your child is hearing. If your child is young it might be best to have only one or two programs, and not let him/her use the Controller. It would be a good idea to visit the audiologist fairly often to make sure the software is still doing what it’s supposed to be doing. Finally, insuring the lot would be smart since the accessories are so easy to lose.

If you have decided to get a cochlear implant and are wondering which to get, does the Naída tip the balance in favor of Advanced Bionics? I don’t know, because I know very little about the processors made by the other manufacturers. There is an excellent and very detailed shopping guide here. For example, it says that Bluetooth connectivity is “under development” in Cochlear’s Nucleus 6 and that Med-El doesn’t have it. I wouldn’t make a decision about an implant solely based on the processor, though. The manufacturers always have new products in development. As I noted earlier, I’ve gone through four generations of processors since 2001. Perhaps readers can add information in the comments.

Let me sum up my ideas for how the Naída system could be improved. I’ll divide them into two categories.

Things That Can Be Done Now

- Speed up program-switching and wakeup. (Update: I’m told AB is working on this.)

- Add a texture to the up-volume button.

- Improve the documentation.

- Rename the pediatric T-mike the “small” mike.

- Rename the myPilot and ComPilot for clarity.

- Rename the special-purpose features (UltraZoom, etc.) for clarity.

Longer-Range Ideas

- Replace the myPilot (the “Controller”) with a mobile app.

- Implement auditory scene analysis and possibly offload it to a mobile app.

- Take advantage of other mobile data such as GPS.

- Build Bluetooth directly into the processor body or into a battery.

- Redesign the user’s experience across features and accessories to minimize confusion and frustration.

Clearly, from my perspective there are a lot of things that could be done. The Naída CI Q70 is the first product of a collaboration between companies, and it shows. There’s user interface issues, nomenclature issues, and documentation issues. In addition, as of early 2014 the Naída is very new, and audiologists are still learning all its options and how its programming software works. Mistakes and confusions are inevitable. And my own learning curve is far from complete.

But the fact that this review is over 8,000 words long shows how many new things Advanced Bionics and Phonak have brought to the table. I had only a vague idea of what Bluetooth was before I got the Naída. Now I’m saying, “Maybe you can do this…and this…and this…” The system has created a whole set of possibilities that never existed before. It has also enabled me to hear music better than I’ve heard it in 13 years. These are signal achievements, and they are very exciting.

Advanced Bionics and Phonak have greatly advanced the state of the art with the Naída CI Q70. I look forward with anticipation to refinements and new products.

Go on to my next entry here.

Thanks for the detailed explanation about the Naida. I opted for the Neptune before all of the details about the Naida were made public and I wondered if I should have waited for the Naida. Having read your report, going with the Neptune was probably best for me.

You totally took the words out of my brain! Now how am I going to do a review without looking like I plagiarized yours!? This is a totally awesome review and you’re spot on about music. It does sound so much better than the Harmonys. Now if only can they figure out how to get below the magical 250 mhz and give us more bass/lows.

As for an app, I would love to have one but I think the bigger issue is they will need FDA approval and then there is that fear of the phone getting hacked and us turning into zombies. Scary, eh?

Take care, my friend…

Sam

Thanks Sam! Everyone has a unique perspective, just write what you think without worrying what anyone else has said. That’s all there is to it. As for Bluetooth-enabled processors being hacked, I’d gladly take the risk provided there were adequate safeguards and I knew the warning signals of something being wrong. Technology always comes with a mix of new powers and new dangers, that’s just the way of it.

Wow, Michael — THANK YOU beyond words for taking the time to write this review. It helps me immensely to read another prelingually deafened adult’s description of music as you remember it with hearing aids, and then comparatively over time as a cyborg. I was born profoundly deaf, wore only one hearing aid in the left ear, am a fluent lipreader and have basically no auditory memory.

I chose bilateral simultaneous implants at age 48 and it has been 10 months since activation. What a wild ride! Voices are still meaningless unless I am reading along with a written text and then I can follow the shape of the voice, and music is a completely random, unpredictable mix of a few pleasant swirling patterns and noise overload. Every day is a new day, another step forward on this cyborg journey. With NO doubt, I have found that if I can understand a fraction of what my brain is trying to take in and untangle, then my patience and ability to make sense of this whole process INCREASES exponentially.

In your review, you give me the gift of music in words.

I have wondered all my life why the big deal about music — what IS it?? — and you give me a tiny taste here in your writing.

I may or may not be able to hear very many beautiful details of music for myself in this life, so I appreciate your words that much more.

Thank you!

Robin

A few things:

The T-mic comes in 3 sizes- small, medium, and large.

Small is recommended for children, medium for teens and adult women (and small guys), and large for adult men.

The program switching delay is, according to my audiologist, going to be solved very soon by a software update.

You failed to mention the variety of colors (I choose the bright blue) and the improved T-mic2 design that is light, flexible, and discrete compared to the T-mic on the harmony.

This is brand new technology, there will be a few kinks that need to be worked out.

Thank you so much for this. I find it so helpful and easy to understand. I just was implanted with Naida on Feb. 11, 2014 so this is very helpful. This is an overwhelming experience and getting used to these new noises and hoping my brain kicks in with all the practice I am doing. I used all the Phonak gadgets with my hearing aids so thankful I was familar with them. Next week at my mapping they are giving me a Neptune as a backup that that will be a whole other learnign experience.

Hi Mike, I’d like to join the chorus of people thanking you for the detailed review. As a bilateral Naida user myself, I’d like to add a couple of observations.

You don’t need the myPilot to synchronize the processors. You can remove and replace the batteries (which you can do while the processors are on your ears – just slide them a little bit without raking them off completely) and they reset to program 1, nominal volume. I don’t even own a myPilot – after testing it out, I didn’t see the need. I agree that switching programs is slow. But you can press the program button multiple times to get from, say, program 1 to program 5, without waiting for the intermediate programs.

I don’t have programs for different sound types like music or speech. The only ones beyond my main program are DuoPhone, which allows me to make phone calls even where people with normal hearing have a lot of difficulty, and UltraZoom for those noisy restaurants.

Bluetooth isn’t in the processors because it currently takes too much power. Look for it down the road as they develop lower power versions of Bluetooth.

Have you ever tried plain old headphones with the Harmony or Naida? Boy, it’s one of the best things about the T-mics! Get good headphones – they only cost about as much as one replacement battery or headpiece. Heck, splurge and get a pair of Bose noise-cancelling headphones. It’s 95% as good as direct connect (or streaming via ComPilot) and may be easier in some situations than using the ComPilot.

You can also use DirectConnect with the ComPilot – no need for Bluetooth! Just plug a cable from your source to the jack at the bottom of the ComPilot. The ComPilot recognizes the cable, and announces ‘audio jack.’ I used it on a plane the other day to watch the movie. Nothing on my ears, and I had direct-connect sound quality! When I was tired of a movie, I unplugged the cable, the ComPilot announced ‘Bluetooth audio’ and I was listening to my phone. It’s just about the only time I use the ComPilot.

Have you installed the myNaida app on your phone? My first impression was that it replicated a bunch of the AB marketing material. But it has nicely organized user guides, and a great troubleshooting section, especially when it comes to explaining the multi-color blinking LED. The best part, of course, is that you can have all that information with you without carrying the actual paper manuals.

Auditory scene analysis is really difficult! How could it possibly tell the difference between, say, a Ramones concert, where you may want to hear all of the, um, ‘music,’ and the noise at popular nightclub, where you may want to cut down the noise and hear the person trying to shout something at you? I suppose it would be more desirable if I were to rely on different programs for different situations, but my processors seem to adapt to 99% of the situations for me without any intervention by making adjustments to my single main program.

Even something relatively simple, like auto-telecoil, is often disabled because it switches on and off at inappropriate times.

Again, thank you for the excellent review.

Thanks for all those terrific tips, Howard. Much to learn!

Very detailed, well-written review, full of information that’s just what many people contemplating a CI or a processor upgrade are looking for. After reading your comments on the accessories and interface issues, I am left thinking that for some users, those who are technically-inclined, all the issues will be resolved easily. For others, those who just want something that works with no fussing, perhaps a second version of the Naida with a simplified remote and interface, will suffice.

As a former long-time user of Phonak hearing aids, I related immediately to your comment about hand waving while waiting for the unit to boot up, or change programs. I use a Nucleus 6, and the unit is ready as soon as you turn it on, and switches programs much more quickly, so it can be done.

GN Resound have just released the Resoundlinx, a hearing aid that connects directly to the iPhone, with no intermediate device, so that technology you are wishing for is coming, and hopefully Phonak/AB will introduce something like that soon.

And finally, your description of listening to music–WOW! It sounds as though all the little annoyances you mentioned are sure worth it. Ten years ago, CI recipients did not expect to be able to enjoy listening to music, but for many of us, that’s all changed. And thank you for noting that listening with just one ear (device?) is just not adequate for music. Some of us can only receive one CI, due to insurance or government policies, and we need to find ways to change that. Your review will help as we lobby for change.

Thank you!

Wow! What a terrific write up!! I am so glad that I got a chance to read your review of the Naida CI. I’m awaiting to upgrade from my Harmony. I loved reading your account of your experiences in listening to music, your statement re:music….”being injected intravenously into my soul, and that has to count for something”….- now that is worth waiting for!!

Thank you for sharing this with us!

Thanks so much for enjoying my writing in this entry. I wanted to try to do justice to the experience!

Thanks for the great review of the Naida and accessories. I am still 2 weeks away from my first CI surgery. I had already chosen the AB system before I read your review and was excited to see the new waterproof enclosure and microphone announced last month (May 2014), as much for dust protection as waterproofing since I sometimes do woodworking and construction that gets pretty dusty, though I also get called out in winter storms.

I’m very pleased to read about your experiences with music. It gives me hope for the future. I haven’t been able to enjoy music for 8 years with my hearing aided remaining ear that has gradually degraded after the first ear went. My extensive library of rock, jazz and classical music patiently awaits a time when I might be able to enjoy it again. I can still hear old favorites in my mind the great piano concertos, Miles Davis and sometimes I sing the words from old rock tunes that used to move me so much (as long as no one is around because I have no idea what it sounds like once it leaves my mouth).

Perhaps it was a sign of things to come when my audiophile quality sound system was stolen from storage as I was transitioning between residences. The theft happened right after my first ear suddenly went deaf. The components I had carefully put together were under insured and I never replaced them, instead choosing to downsize and I bought my first iPod, began downloading my digital collection and backing it up. I gave my old vinyl music treasures to friends who still keep collections and equipment to play them on.

I wish I had read this before my Med-El CI was implanted. It was advertised as having “Automatic Sound Management.” That sounded impressive, but is only automatic gain control (AGC).

That is like advertising a car with a Collision Avoidance System and finding out that the system consists on a steering wheel and breaks. You cannot have a CI processor without AGC anymore than you can have a car without a steering wheel and breaks.

Med-El was also claimed its fine structure would make music sound better. It doesn’t… at least not for

me. Music is just noise.

Hello!

I read your blog. Wonderful information. Can you tell me please what’s or how is your experience with Naida and phones? Cell phones it’s ok..not 100% for me, however it’s ok, but when it comes to use the ofc phones that’s when I have a hard time understanding what are they saying or if they are telling me their last name etc?

if you have any tips or suggestions please let me know. I’ll ordering the t-mic pediatric to see if it’s a better fit for me.

Also..a lot of times i can hear or understand at all in restaurants or when I find myself in a group of people. I can’t follow conversation. having a hard time with Naida.